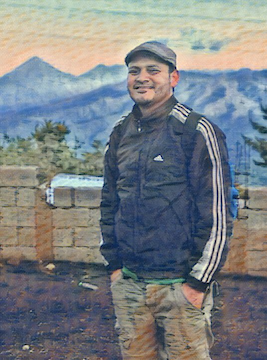

Dr. Leonel González de León is an infectious diseases physician at Hospital del Seguro Social, a public hospital for people with social security, based in Guatemala City, the capital of Guatemala.

What is your background?

I was born in Antigua. I went to Catholic school. Then when I was seventeen, I finished high school and I got a scholarship to study medicine in Cuba. I became a doctor in Havana, Cuba and lived there for seven years.

What got you interested in medicine?

Since I was a child, I was curious about the human body. How it works, how it grows, how it ages, how we can heal, how we change and how we die. That was my main curiosity since I was a child, and then I went to medical school.

Did you always know you wanted to be a doctor?

Absolutely. I never had a doubt. I can't see myself being anything else. My grandmother was a nurse and she came back home, exhausted from night shifts. I asked her “How do you work that much? Why do you work that much?”

“Because in hospitals you have to. People are ill. They pass away in the night. You have to look after them.” I was very curious about it.

Where did you go to medical school, and when did you become interested in infectology?

Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina. I first learned about germs, bacteria, and viruses in my second year of medicine and I always had a curiosity. I admire bacteria. I admire viruses because we will never catch them. They are much wiser than we are. They can adapt themselves. That's a miracle.

Can you talk about the hospital where you work?

It's the most important hospital for people who have social security. It's a small public hospital with maybe 300, 400 beds, but it has to receive people with critical diseases or surgical diseases from the whole country. and it's always crowded, very full, beyond its capacity.

What does a typical day at work look like for you?

I see infectious diseases all day long, such as HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis. I come in at seven and then I go to the hospital. I go to the wards and I meet with infectious patients. I meet them after their labs. I challenge them and I advise which antibiotic this patient should have.

Tell us about your team.

We are six physicians in infectious diseases. We care about complicated infections. We deal with HIV diagnosis, counseling and treat opportunistic infections. We work rounds. We are divided into several areas in the hospital. I work in the laboratory, personal care unit, and external consult for ambulatory patients, who only come for prescriptions.

Tell us about your patients.

I see people from the whole country because the hospitals are here in the city. There are no infectologists anywhere else in the country. I don’t see anyone younger than 15. We see people with acute infections and with chronic infections. There are complicated patients with severe infections. The older patients are the most complicated.

What are the challenges in your work?

Crowding, lack of personnel for support or coverage. As a poor country, we lack everything: soap, beds, wards, labs, and medication. Guatemala has 15 million inhabitants. Let's assume that one-third of them have social security; that’s five million. And let's assume that half of them are adults. That is two and a half million people, and we are only six infectologists for this population.

Sometimes your patients don’t make it. How do you handle death as a part of your work?

Death is not only a part of medical work. It is a complementary part of life. We must get used to it so that we don’t cry with every patient that passes away.

What are the languages you use now and have used in the past with patients?

Everyone speaks Spanish in my hospital. But if you go to other public health hospitals, you find many people who do not speak Spanish. We have more than twenty languages here. After finishing school, I worked for two years in Santiago Atitlán in the Centro de Atención de Partos (Delivery Center). I learned some Tzutuhil, the native language from people around Atitlán Lake.

How does trust play a part in your work?

The patient is putting his life, his dreams, his fears, his pain─he’s putting himself into your hands. You must gain your patients’ confidence. That's the only way to do good medicine.

What are you most proud of about your work?

To learn from patients and being able to teach medicine to younger doctors or medical students who come behind me.

Was there any special moment in your career as a doctor?

Having great teachers; having great professors who had the patience to teach me. I am proud and glad that I had those fantastic teachers in Cuba.

What is the best life or career advice you have received?

It was not advice. It was a warning. When I was 16 or 17 and I was finishing high school, I said: "Grandma, I am studying medicine!” She sat and she told me, it's going to be very hard; it's going to be exhausting. You will be absent for Christmas, holidays, your birthday and so on. Are you willing to miss all of those important occasions in the family? If so, go into medical school. If not, do something else.

What advice do you have for a healthcare provider just starting out?

What advice do you have for a healthcare provider just starting out?

Be grateful to your patients. Be grateful today because of how much a patient teaches us. We would be nothing without patients. Take every minute with your patient. Seeing and listening to the patient gives you the diagnosis much more accurately than labs or images.

When you have free time outside of work, how do you like to spend it?

I read literature, I write and I like to do sports. Mountain hiking, bicycling. It's also necessary as a therapy to get rid of stress.

More Stories from Kinnected

At times, it has been really frustrating to be a strategist and health communication professional and witness the lack of strategic planning and messaging that we have over the last two years.

-

4 years ago

"What many people miss is that emotional exhaustion among clinicians existed long before the pandemic."

-

4 years ago

"A lot of people argue whether technology is good for the future of humanity or bad. In my opinion, it is both - just as an herb could be a poison or a medicine."

-

4 years ago